The Gypsies

1 When spring comes, the drom

(“road”) beckons all Roms, as the Gypsies call themselves. Whether they

are nomads who have stopped for the winter or sedentary Gypsies living

in cities, their hearts are awakened. They believe that all land under

their feel is their own.

2 José,

a Gypsy of Arles, in Provence, once told me about his youth before

World War II, when he traveled with his large family in a horse-drawn

caravan to Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, the west coast of

France, through the Pyrenees, Montpelier, and then back to Arles again

by autumn, making the same circuit year after year, selling horses and

rugs and doing metalwork. "We went everywhere. We stopped in the fields,

amused ourselves in the trees. If we wanted a fruit, we ate it. We were

savage. We were free."

3 The

Gypsies, it is thought, wandered out of Central Asia about 4,000 years

ago. They have never stopped moving. They arrived in Europe in the late

Middle Ages, and used the annual religious pilgrimages they found there

as pretexts for large tribal gatherings, since they ordinarily traveled

in small groups to avoid the authorities. At the gatherings, they

conducted family business-baptisms, marriages, trials-and exchanged

news.

4 This

tradition continues today. Every May, Gypsies from all over Europe

gather in the village of Les Saintes Maries-de-la Mer, in the south of

France, to venerate their partron saint, Sara-Kali. The campgrounds are

filled with trailers, clotheslines, and cooking fires. Inside each

caravan, the entire family sleeps crowded together on the floor under

feather quilts. Although they live communally, Gypsies preserve their

privacy through mutual respect and strict codes of behavior; they feel

there is something wrong with a man who needs to hide behind walls.

5 The

Gypsy is happiest in the natural world, where he can hear the rain at

night on his caravan and smell the woods. He lives from day to day, and

he likes uncertainty. He has known practically from infancy that sudden

changes from comfort to discomfort are essential for a healthy life. As a

result, he has a deep sense of self-reliance.

6 Today

many Gypsies have moved into the cities (there are communities in

Boston, New York, Newark, and Los Angeles) or have been forced into

"settlements." But they paint their ceilings blue to remind themselves

of the sky, and they cover their walls with rugs to bring back the

feeling of a tent. "We don't like fancy houses," José says. "We like an

old house with a fireplace for heat and cooking. We eat with the

fingers-no need for forks or spoons. We are free like that, and it is

becauseof this that the Romany will never change. We wil always stay as

we were born."

PATRICIA FOLLMER1

_____________

1"The

Gypsies" by Patricia Follmer. Copyright 1974 by Harper's Magazine.

Reprinted form the July 1974 issue by special permission.

HARBRACE COLLEGE HANDBOOK

ISBN: 0-15-531824-1

|

|

Observe how Patricia Follmer1 effectively arranges and

expresses her ideas as she explains the attitudes and traditions of the

nomadic Gypsies (her central idea). Notice that every paragraph sticks

to the subject and refers to the titles. Give special attention to the

close relationship between the beginning and the ending of the

composition.

|

Planning and Writing the Whole Composition .................................................................................... Arrange and express your ideas effectively.

A

paragraph is usually a series of sentences developing one controlling

idea: A paragraph developed by causal analysis must not only raise the

question why but answer it to the satisfaction. The cause or causes must

satisfactorily explain the result.

Many good paragraphs are

developed not by any one specific method but by a combination of

methods. Some good paragraphs almost defy analysis. The important

consideration is not the specific method used but the adequacy of the

development.

A whole composition is usually a series of

paragraphs developing several closely related facets of one controlling,

or central, idea.

Notice that every paragraph sticks to the

subject and refers to the title. Give special attention to the close

relationship between the beginning and the ending of the composition.

A

unified composition, whether only one paragraph or a series of

paragraphs, does not fall into order by chance. Order is the result of

careful planning.

Choose an appropriate subject and limit it properly.

A subject is properly limited if you can treat it adequately (according to your purpose) in the time and space at your disposal.

Here are two examples of ways that a subject may be limited:

speed skating =>contests on ice => the winter games => the Olympics => Sports

cyclamate-sweetened peaches => cyclamates => additives => food preparation =>Domestic arts

Deciding on the degree of limitation is a matter of the writer’s judgment.

PURPOSE

Before

making a final decision regarding the specific topic, you should

consider your purpose in writing the composition. Suppose, for example,

that you have chosen (or have been assigned) “American Burial Customs”

as a general subject for a short paper. If your main purpose is to

inform the reader, either “Kinds of Floral Arrangements for Coffins” or

“Some Burial Customs Are Dying Out” would be appropriate. To arouse

interest, you might write a story about a person who has trouble

arranging for his or her own burial—perhaps by mail order.

Although

you may have secondary aims, each of the primary purposes you might

select corresponds to one of the four main types of writing as they are

conventionally classified in rhetoric:

Type of writing--------Primary purpose

Exposition...............To inform or explain

Argumentation.........To convince or persuade

Narration.................To entertain or interest

Description..............To describe or picture

Exposition

(often combined with description and/or bits of narration) is the most

common type of nonfiction and the kind most frequently written by

college students. “How-to” compositions, for instance, are expository.

Dealing with facts and ideas, expository compositions may define

identify, classify, illustrate, compare, contrast, or explain a process.

Argumentation

(often blended with exposition, as well as with other types of writing)

is concerned with the validity of a theory, thesis, or proposition and

gives reasons why it is true or false.

Narration

(generally blended with description) focuses on action: simple stories

(like newspaper stories) present events in chronological order;

narratives with plots involve setting, characterization, conflict.

Description

(seldom written independently, but usually a part of narration,

exposition, argument) presents a picture with details that convey a

sensory impression. Few compositions are a single form of discourse.

Most are mixtures in which one form predominates.

CENTRAL IDEA

After

deciding on your purpose, you will find it helpful to set down, in a

single sentence, the central or controlling idea for your paper. In

fact, if in the beginning you can set down a central idea containing

logically arranged main points, you will already have the main plan and

perhaps eliminate the need for a formal outline.

1. Purpose: To inform by pointing out ways to appraise a used car [Exposition]

Title: How to Buy a Good Used Car

Central

idea: Before selecting a used car, a wise buyer will carefully inspect

the car, talk to the former owner of the car, and engage a good mechanic

to examine its motor.

2. Purpose: To convince the reader of a need for change in the examination system [argument]

Title: Why Have Final Examinations?

Central idea: Final examinations should be abolished.

3. Purpose: To tell a story about a true experience [Narration]

Title: Dangerous Waters

Central idea:

Looking for dolphin twenty miles out, I steered my light fishing boat

into dangerous waters and spent hours battling high winds before being

rescued.

4. Purpose: To describe my girlfriend and show how she manages to get her own way with others. [Exposition, description, narration]

Title: Who Can Say No to Her?

Central idea: My girlfriend gets her way because of her “endearing young charms.”

Choose one of the subjects.

1. radio

2. dress

3. endangered species

4. overpopulation-fact or fiction?

The

first step in the preparation of a rough outline is the jotting down of

ideas on the topic. Write strong opinions on the subject and decide to

compare. Next, choose a tentative title, and then jot down ideas related

to the title. Then formulates a central idea, singles out key ideas,

and arrnges them in a logical order, decide on the title, and writes out

the plan.

Use a formal outline of the type specified by instructor.

The types of outlines most commonly used are the sentence outline, the topic outline, and the paragraph outline.

Topic

outlines and sentence outlines have the same parts and the same

groupings; they differ only in the fullness of expression employed. In a

paragraph outline no effort is made to classify the material into major

headings and subheadings; the controlling idea (stated or implied) of

each paragraph is simply listed in the order in which it is to come.

Paragraph outlines are especially helpful in writing short papers. Topic

or sentence outlines may be adapted to papers of any length.

◙ ◙ ◙TOPIC OUTLINEA New Silent GenerationCentral idea:Today's generation is as silent as the 1950s generation but does not have its illusions.

Introduction: The silence on American campuses is disturbing.

I. The silent generation of the 1950s

A. Opportunistic acceptance of world

B: Confidence in self and country

II. The silent generation of today

A: Disillusioning experiences

B: Economic uncertainty

C: Political attitude

Conclusion: This retreat to the 1950s has left an enormous gap in American life.

◙ ◙ ◙SENTENCE OUTLINEA New Silent GenerationCentral idea: Today's generation is as silent as the 1950s generation but does not have its illusions.

Introduction: The silence on American campuses is disturbing.

I. The college generation of the 1950s wa silent.

A. Students opportunistically accepted their world.

B. They felt secure as students and as Americans.

II. Today's generation is silent.

A. Students have lived through disillusioning times.

B. They face great economic uncertainties.

C: They have become disgusted with politics.

Conclusion: This retreat to the 1950s has left an enormous gap in American life.

◙ ◙ ◙PARAGRAPH OUTLINE1. A disturbing silence has fallen over American campuses.

2. Are we back in the 1950?

3. The 1950s college generation accepted the world they lived in.

4. Because of their memories and experiences, today's college students have no such illusions.

5. There is great economic uncertainty.

6. Today's youth are disgusted with and have retreated from politics.

7. This retreat has left a big gap in American life.

◙ ◙ ◙Topic and sentence outlines and indention for parallel structure.Any

intelligible system of notation is acceptable. The one used for both

the topic outline and the sentence outline is in common use. This

system, expanded to show subheadings of the second and third degrees, is

as follows:

I. ........................[Used for major headings]

A. .....................[Used

for subheadings of the first

degree]

B. ......................[Used

for subheadings of the first

degree]

1. .......................[Used

for subheadings of the second

degree]

2. .......................[Used

for subheadings of the second

degree]

a. .....................................[Used

for subheadings of

the

third degree]

b.

................................[Used for subheadings of

the

third degree]

II. .......................

Seldom, however, will a short outline-or even a longer one-need subordination beyond the first or second degree.

Use

parallel structure for parallel parts of the topic outline to clarify

the coordination of parts. In topic outlines, the major headings (I, II,

III, and so on) should be expressed in parallel structure, as should

each group of subheadings. But it is unnecessary to strive for parallel

structure between different groups of subheadings-for example, between

A, B, and C under I and A, B, and C under II. (Parallel structure is not

a concern in either the sentence outline or the paragraph outline.)

◙ ◙ ◙EFFECTIVE BEGINNNGS AND ENDINGS Every composition needs an effective beginning and ending.

One

of the best ways to begin is with a sentence that not only arouses the

reader's interest but also sets forth the first main point and starts

its development.

Another way to begin a composition is to write

an introductory paragraph that arouses interest and states the central

idea of the composition but does not start the development of the first

main point.

Still another way to begin is with a question. The

answer to it may set forth the main points to be discussed later. A

transitional paragraph may intervene between the introduction and the

discussion of the first main point.

A composition should end; it

should not merely stop. Two ways to end a composition effectively are to

stress the final point of the main discussion by using an emphatic last

sentence and to write a strong concluding paragraph. Often a concluding

paragraph clinches, restates, or stresses the importance of the central

idea or thesis of the composition. An effective ending may also present

a summary, a thought-provoking question, a solution to a problem, or a

suggestion or challenge.

Caution: Do not devote

too much space to introductions and conclusions. A short paper often has

only one paragraph for a beginning or an ending; frequently one

sentence for each is adequate. Remember that the bulk of your

composition should be the development of the central idea, the

discussion of the main headings and subheadings in your outline.

Planning and Writing the Whole Composition.................................................................................... Arrange and express your ideas effectively.

A

paragraph is usually a series of sentences developing one controlling

idea: A paragraph developed by causal analysis must not only raise the

question why but answer it to the satisfaction. The cause or causes must

satisfactorily explain the result.

Many good paragraphs are

developed not by any one specific method but by a combination of

methods. Some good paragraphs almost defy analysis. The important

consideration is not the specific method used but the adequacy of the

development.

A whole composition is usually a series of

paragraphs developing several closely related facets of one controlling,

or central, idea.

Notice that every paragraph sticks to the

subject and refers to the title. Give special attention to the close

relationship between the beginning and the ending of the composition.

A

unified composition, whether only one paragraph or a series of

paragraphs, does not fall into order by chance. Order is the result of

careful planning.

Choose an appropriate subject and limit it properly.

A subject is properly limited if you can treat it adequately (according to your purpose) in the time and space at your disposal.

Here are two examples of ways that a subject may be limited:

speed skating =>contests on ice => the winter games => the Olympics => Sports

cyclamate-sweetened peaches => cyclamates => additives => food preparation =>Domestic arts

Deciding on the degree of limitation is a matter of the writer’s judgment.

PURPOSE

Before

making a final decision regarding the specific topic, you should

consider your purpose in writing the composition. Suppose, for example,

that you have chosen (or have been assigned) “American Burial Customs”

as a general subject for a short paper. If your main purpose is to

inform the reader, either “Kinds of Floral Arrangements for Coffins” or

“Some Burial Customs Are Dying Out” would be appropriate. To arouse

interest, you might write a story about a person who has trouble

arranging for his or her own burial—perhaps by mail order.

Although

you may have secondary aims, each of the primary purposes you might

select corresponds to one of the four main types of writing as they are

conventionally classified in rhetoric:

Type of writing--------Primary purpose

Exposition...............To inform or explain

Argumentation.........To convince or persuade

Narration.................To entertain or interest

Description..............To describe or picture

Exposition

(often combined with description and/or bits of narration) is the most

common type of nonfiction and the kind most frequently written by

college students. “How-to” compositions, for instance, are expository.

Dealing with facts and ideas, expository compositions may define

identify, classify, illustrate, compare, contrast, or explain a process.

Argumentation

(often blended with exposition, as well as with other types of writing)

is concerned with the validity of a theory, thesis, or proposition and

gives reasons why it is true or false.

Narration

(generally blended with description) focuses on action: simple stories

(like newspaper stories) present events in chronological order;

narratives with plots involve setting, characterization, conflict.

Description

(seldom written independently, but usually a part of narration,

exposition, argument) presents a picture with details that convey a

sensory impression. Few compositions are a single form of discourse.

Most are mixtures in which one form predominates.

CENTRAL IDEA

After

deciding on your purpose, you will find it helpful to set down, in a

single sentence, the central or controlling idea for your paper. In

fact, if in the beginning you can set down a central idea containing

logically arranged main points, you will already have the main plan and

perhaps eliminate the need for a formal outline.

1. Purpose: To inform by pointing out ways to appraise a used car [Exposition]

Title: How to Buy a Good Used Car

Central

idea: Before selecting a used car, a wise buyer will carefully inspect

the car, talk to the former owner of the car, and engage a good mechanic

to examine its motor.

2. Purpose: To convince the reader of a need for change in the examination system [argument]

Title: Why Have Final Examinations?

Central idea: Final examinations should be abolished.

3. Purpose: To tell a story about a true experience [Narration]

Title: Dangerous Waters

Central idea:

Looking for dolphin twenty miles out, I steered my light fishing boat

into dangerous waters and spent hours battling high winds before being

rescued.

4. Purpose: To describe my girlfriend and show how she manages to get her own way with others. [Exposition, description, narration]

Title: Who Can Say No to Her?

Central idea: My girlfriend gets her way because of her “endearing young charms.”

Choose one of the subjects.

1. radio

2. dress

3. endangered species

4. overpopulation-fact or fiction?

The

first step in the preparation of a rough outline is the jotting down of

ideas on the topic. Write strong opinions on the subject and decide to

compare. Next, choose a tentative title, and then jot down ideas related

to the title. Then formulates a central idea, singles out key ideas,

and arrnges them in a logical order, decide on the title, and writes out

the plan.

Use a formal outline of the type specified by instructor.

The types of outlines most commonly used are the sentence outline, the topic outline, and the paragraph outline.

Topic

outlines and sentence outlines have the same parts and the same

groupings; they differ only in the fullness of expression employed. In a

paragraph outline no effort is made to classify the material into major

headings and subheadings; the controlling idea (stated or implied) of

each paragraph is simply listed in the order in which it is to come.

Paragraph outlines are especially helpful in writing short papers. Topic

or sentence outlines may be adapted to papers of any length.

◙ ◙ ◙TOPIC OUTLINEA New Silent GenerationCentral idea:Today's generation is as silent as the 1950s generation but does not have its illusions.

Introduction: The silence on American campuses is disturbing.

I. The silent generation of the 1950s

A. Opportunistic acceptance of world

B: Confidence in self and country

II. The silent generation of today

A: Disillusioning experiences

B: Economic uncertainty

C: Political attitude

Conclusion: This retreat to the 1950s has left an enormous gap in American life.

◙ ◙ ◙SENTENCE OUTLINEA New Silent GenerationCentral idea: Today's generation is as silent as the 1950s generation but does not have its illusions.

Introduction: The silence on American campuses is disturbing.

I. The college generation of the 1950s wa silent.

A. Students opportunistically accepted their world.

B. They felt secure as students and as Americans.

II. Today's generation is silent.

A. Students have lived through disillusioning times.

B. They face great economic uncertainties.

C: They have become disgusted with politics.

Conclusion: This retreat to the 1950s has left an enormous gap in American life.

◙ ◙ ◙PARAGRAPH OUTLINE1. A disturbing silence has fallen over American campuses.

2. Are we back in the 1950?

3. The 1950s college generation accepted the world they lived in.

4. Because of their memories and experiences, today's college students have no such illusions.

5. There is great economic uncertainty.

6. Today's youth are disgusted with and have retreated from politics.

7. This retreat has left a big gap in American life.

◙ ◙ ◙Topic and sentence outlines and indention for parallel structure.Any

intelligible system of notation is acceptable. The one used for both

the topic outline and the sentence outline is in common use. This

system, expanded to show subheadings of the second and third degrees, is

as follows:

I. ........................[Used for major headings]

A. .....................[Used

for subheadings of the first

degree]

B. ......................[Used

for subheadings of the first

degree]

1. .......................[Used

for subheadings of the second

degree]

2. .......................[Used

for subheadings of the second

degree]

a. .....................................[Used

for subheadings of

the

third degree]

b.

................................[Used for subheadings of

the

third degree]

II. .......................

Seldom, however, will a short outline-or even a longer one-need subordination beyond the first or second degree.

Use

parallel structure for parallel parts of the topic outline to clarify

the coordination of parts. In topic outlines, the major headings (I, II,

III, and so on) should be expressed in parallel structure, as should

each group of subheadings. But it is unnecessary to strive for parallel

structure between different groups of subheadings-for example, between

A, B, and C under I and A, B, and C under II. (Parallel structure is not

a concern in either the sentence outline or the paragraph outline.)

◙ ◙ ◙EFFECTIVE BEGINNNGS AND ENDINGS Every composition needs an effective beginning and ending.

One

of the best ways to begin is with a sentence that not only arouses the

reader's interest but also sets forth the first main point and starts

its development.

Another way to begin a composition is to write

an introductory paragraph that arouses interest and states the central

idea of the composition but does not start the development of the first

main point.

Still another way to begin is with a question. The

answer to it may set forth the main points to be discussed later. A

transitional paragraph may intervene between the introduction and the

discussion of the first main point.

A composition should end; it

should not merely stop. Two ways to end a composition effectively are to

stress the final point of the main discussion by using an emphatic last

sentence and to write a strong concluding paragraph. Often a concluding

paragraph clinches, restates, or stresses the importance of the central

idea or thesis of the composition. An effective ending may also present

a summary, a thought-provoking question, a solution to a problem, or a

suggestion or challenge.

Caution: Do not devote

too much space to introductions and conclusions. A short paper often has

only one paragraph for a beginning or an ending; frequently one

sentence for each is adequate. Remember that the bulk of your

composition should be the development of the central idea, the

discussion of the main headings and subheadings in your outline.

Tips for Memo Reports

• Use memo format for most short (eight or fewer papers) informal reports within an organization.

• Leave side margins of 1 to 11/4 inches.

• Sign your initials on the FROM line.

• Use an informal, conversational style.

• Include talking (descriptive) or functional side headings to organize a report into logical divisions.

• For a receptive audience, put recommendations first.

• For an unreceptive audience, put recommendations last.

|

Monday, August 20, 2012 2:26:50 AM

Writing Composition

Outlines and Headings

Most writers agree that the clearest way to show the organization of a

report topic is by recording its divisions in an outline. Although the

outline is not part of the final report, it is a valuable tool of the

writer. It reveals at a glance the overall organization of the report.

Outlining involves dividing a topic into major sections and supporting

those with details.

Rarely is a real outline so perfectly balanced; some sections are

usually longer than other. Remember, though, not to put a single topic

under a major component. If you have only one subpoint, integrate it

with the main item above it or reorganize. Use details, Illustrations,

and evidence to support subpoints.

The main points used to outline a report often become the main headings

of the written report. Formatting those headings depends on what level

they represent. Major headings are centered and typed in bold font.

Second-level heađings start at the left margin, and third-level headings

are indented and become part of a paragraph.

|

****

Topic and Sentence Outlines

and

Indention for Parallel Structure.

Use parallel structure for parallel parts of the topic outline to

clarify the coordination of parts. In topic outlines, the major headings

(I, II, III, and so on) should be expressed in parallel structure, as

should each group of subheadings.

Any intelligible system of notation is acceptable. The one used for both

the topic outline and the sentence outline is in common use. This

system, expanded to show subheadings of the second and third degrees, is

as follows:

I. .......................[Used for major headings]

A. .....................[Used for

subheadings of the

first

degree]

B. .....................[Used for

subheadings of the

first

degree]

1. ..................[Used

for subheadings of the

second

degree]

2. ..................[Used

for subheadings of the

second

degree]

a. ...............[Used

for subheadings of the

third

degree]

b. ...............[Used

for subheadings of the

third

degree]

II. .......................

|

Outlines and Parallel Structure

I. ............................................................

A. ............................................................

B. ............................................................

C. ............................................................

D. ............................................................

II. ............................................................

A. ............................................................

III. ............................................................

A. ............................................................

IV. ............................................................

A. ............................................................

1. ............................................................

B. ............................................................

1. ............................................................

a. ............................................................

b. ............................................................

c. ............................................................

C. ............................................................

1. ............................................................

2. ............................................................

V. ............................................................

A. ............................................................

B. ............................................................

C. ............................................................

|

OUTLINE

The Rise of the New Deal Order

I. Your musical introduction

A. Row, Row, Row With Roosevelt

B. Roosevelt, Garner, and Me

C. Happy Days Are Here Again

D. F.R.'s First Inauguration Speech

II. Historical Question

A. Was the New Deal a radical social reform program?

III. Thesis

A.

Roosevelt's haphazard program of New Deal reforms brought radically new

approaches to American social reform. The expansion of the federal

government, redefinitons of poverty andi its causes, as well as a social

welfare system that has become a stple of all subsequent presidential

administrations testify to the New Deal's seminal importance in American

political and social life.

IV. The "New" Deal

A. The Expansion of the Federal Government

1. The 100 Days and Alphabet Soup

B. Redefinitions of Poverty

1.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration

a.

Harry Hopkins, Spending To Save

b.

Local government

c.

A New Deal for Blacks?

C. Social Welfare

1. The Second New Deal

2. The Social Security of 1935

V. Suggestions for further reading include:

A. Michael Moore's video Roger and Me offers great insights into 1930s working-class history. Rent it at your local video store.

B. Lizbeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1930

C. Alan Brinkley, Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression

|

Outlines and Parallel Structure

bgcolor="#e2e8d6"

font style="color: rgb(51, 102, 102)

Square Brackets [ ]

Origin: Development of the Language

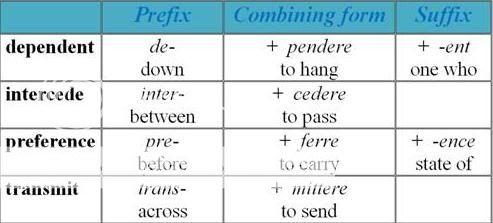

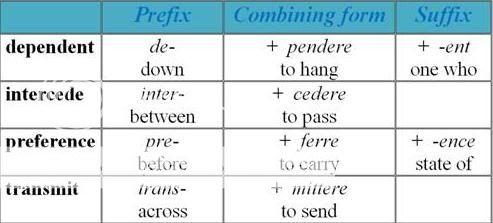

In college dictionaries the origin of the word—also called its

derivation or etymology—is shown in square brackets. For example, after

expel might be this information: “[< ex- out + pellere to drive, thrust].” This means that expel is derived from (<) the Latin (L) word expellere,

which is made up of ex-, meaning “out,” and the combining form peller,

meaning “to drive or thrust.” Breaking up a word, when possible, into

prefix (and also suffix, if any) and combining form, as in the case of

expel, will often help to get at the basic meaning of a word.

The bracketed information given by a good dictionary is especially rich

in meaning when considered in relation to the historical development of

our language. English is one of the Indo-European (IE)2[1]

language, a group of languages apparently derived from a common source.

Within this group of languages, many of the more familiar words are

remarkably alike. Our word mother, for example, is mater in Latin (L),

meter in Greek (Gk.), and matar in ancient Persian and in the Sanskrit

(Skt.) of India. Words in different languages that apparently descend

from a common parent language are called cognates. The large number of

cognates and the many correspondences in sound and structure in most of

the languages of Europe and some languages of Asia indicate that they

are derived from the common language that linguists call Indo-European,

which it is believed was spoken in parts of Europe about five thousand

years ago. By the opening of the Christian era the speakers of this

language had spread over most of Europe and as far east as India, and

the original Indo-European had developed into eight or nine language

families. Of these, the chief ones that influenced English were the

Hellenic (Greek) group on the eastern Mediterranean, the Italic (Latin)

on the central and western Mediterranean and Germanic in northwestern

Europe.

English is descended from the Germanic. Two thousand years ago the

Hellenic, the Italic, and the Germanic branches of Indo-European each

comprised a more or less unified language group. After the fall of the

Roman Empire in the fifth century, the several Latin-speaking divisions

developed independently into the modern Romance languages, chief of

which are Italian, French, and Spanish. Long before the fall of Rome the

Germanic group was breaking up into three families:

(1) East Germanic, represented by the Goths, who were to play a large

part in the history of the last century of the Roman Empire before

losing themselves in its ruins;

(2) North Germanic, or Old Norse (ON), from which we have modern Danish

(Dan.) and Swedish (Sw.), Norwegian (Norw.) and Icelandic (Icel.); and

(3) West Germanic, the direct ancestor of English, Dutch (Du.), and German (Ger.).

The English language may be said to have begun about the middle of the

fifth century, when the West Germanic Angles, Saxons, and Jutes began

the conquest of what is now England and either absorbed or drove out the

Celtic-speaking inhabitants. (Celtic—from which Scots Gaelic, Irish

Gaelic, Welsh, and other languages later developed—is another member of

the indo-European family.) The next six or seven hundred years are known

as the Old English (OE) or Anglo-Saxon (AS) period of the English

language. The fifty or sixty thousand words then in the language was

chiefly Anglo-Saxon, with a small mixture of Old Norse words as a result

of the Danish (Viking) conquests of England beginning in the eighth

century. But the Old Norse words were so much like the Anglo-Saxon that

they cannot always be distinguished. The transitional period

from Old English to Modern English—about 1100 to 1500—is known as

Middle English (ME). The Norman Conquest began in 1066. The Normans, or

“Northmen,” had settled in northern France during the Viking invasions

and had adopted Old French (OF) in place of their native Old Norse.

Then, crossing over to England by the thousands, they made French the

language of the king’s court in London and of the ruling classes—both

French and English—throughout the land, while the masses continued to

speak English. Only toward the end of the fifteenth century did English

become once more the common language of all classes. But the language

that emerged at that time had lost most of its Anglo-Saxon inflections

and had taken on thousands of French words (derived originally from

Latin). Nonetheless, it was still basically English, not French, in its

structure.

The marked and steady development of the English language (until it was

partly stabilized by printing, which was introduced in London in 1476)

is suggested by the following passages, two from Old English and two

from Middle English. A striking feature of Modern English

(that is, English since 1500) is its immense vocabulary. As already

noted, Old English used some fifty or sixty thousand words, very largely

native Anglo-Saxon; Middle English used perhaps a hundred thousand

words, many taken through the French from Latin and others taken

directly from Latin; and unabridged dictionaries today list over four

times as many. To make up this tremendous word hoard, we have borrowed

most heavily from Latin, but we have drawn some words from almost every

know language. English writers of the sixteenth century were especially

eager to interlace their works with words from Latin authors. And, as

the English pushed out to colonize and to trade in many parts of the

globe, they brought home new words as well as goods. Modern science and

technology have drawn heavily from the Greek. As a result of all this

borrowing, English has become the richest, most cosmopolitan of all

languages.

In the process of enlarging our vocabulary we have lost most of our

original Anglo-Saxon words. But those that are left make up the most

familiar, most useful part of our vocabulary. Practically all our simple

verbs, our articles, conjunctions, prepositions, and pronouns are

native Anglo-Saxon; and so are many of our familiar nouns, adjectives,

and adverbs. Every speaker and writer uses these native words over and

over, much more frequently than the borrowed words. Indeed, if every

word is counted every time it is used, the percentage of native words

runs very high—usually between 70 and 90 percent. Milton’s percentage

was 81, Tennyson’s 88, Shakespeare’s about 90, and that of the King

James Bible about 94. English has been enriched by its extensive

borrowings without losing its individuality; it is still fundamentally

the English language.

__________________

[1] /2 The parenthetical abbreviations for languages

here and on the next few pages are those commonly used in bracketed

derivations in dictionaries.

|

************************************************************

Memorandum

[mem-uh-ran-duh m]

mem·o·ran·dum

ˌmeməˈrandəm/Submit

noun

a written message, especially in business or diplomacy.

"he told them of his decision in a memorandum"

synonyms: message, communication, note, email, letter, missive, directive; More

a note or record made for future use.

"the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding on economic cooperation"

synonyms: message, communication, note, email, letter, missive, directive; More

LAW

a document recording the terms of a contract or other legal details.

Although e-mail is more often used, hard-copy memos are still useful for

important internal messages that re quire a permanent record or

formality.

MEMO TO: Diana E. McNabb, City Manager

FROM: Paul Dollar, Street Department Director

DATE: October 9, 2010

SUBJECT: Deer Run Street Problem

As you know, there has been extensive development of the housing area on

the East Side, commonly known as Deer Run. The project coordinator

informed me just the other day that about five new homes are started

each week.

A petition has been received from residents of the area stating that

builders have been ignoring city regulations relating to the banning of

lugged wheels from city streets. When moving a short distance,

bulldozers commonly are seen moving on the streets rather than being

transported on trailers. A copy of the petition is attached.

The residents have also expressed concerns over the following service interruptions:

1. Television cable was severed five times in one week.

2. Telephone service was interrupted four times in two weeks due to damage to the main telephone line.

3. City water lines were broken two times with interruption of water service for extended periods of time.

4. Electric service is frequently interrupted.

As this may be a delicate matter, I felt that I should contact you

before informing the city attorney’s office about the matter. I am

hopeful that you will provide appropriate advice to me within a day or

two.

ltn

Attachment

|

MEMO TO: Luis Torres, General Manager

FROM: Jonathan R. Evans, Assistant Marketing Manager

DATE: January 12, 200x

SUBJECT:

An Analysis of the Scope and Effectiveness of

Online

Advertising

Here is the report analyzing the scope and effectiveness of Internet advertising that you requested on January 5, 200x.

The report predicts that the total value of the business-to-business

e-commerce market will reach $1.3 trillion by 2003, up from $190 billion

in 1999. New technologies aimed at increasing Internet ad interactivity

and the adoption of standards for advertising response measurement and

tracking will contribute to this increase. Unfortunately, as discussed

in this report, the use of "rich media" and interactivity in Web

advertising will create its own set of problems.

I enjoyed working on this assignment, Luis, and I learn quite a bit

from my analysis of the situation. Please let me know if you have any

questions about the report.

plw

Attachment

|

|

A

letter or memo of transmittal announces the report topic and explain

who authorized it. It briefly describes the project and previews the

conclusions, if the reader is supportive. Such messages generally close

by expressing appreciation for the assignment, suggesting follow-up

actions, acknowledging the help of others, or offering to answer

questions. The margins for the transmittal should be the same as tor the

report, about 1 to 11/4 inches on all sides. The letter should be left-justified. A page number is optional.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment